by Auke van der Woud (1947-)

Groningen:

cultureel maandblad,

ISSN 0011-2941

vol. 16 (1974-1975), pp. 57-74;

provided by Koos Halsema

translated by Anja Van Dam

Nota Bene:

a Waterstaat = Department of Public Works, i.e. department for the maintenance of buildings, dikes, roads, bridges and the navigability of canals.

a kerk = church

a ƒ = Dutch guilder (=florijn=fl)

The “Waterstaatskerk” and the neo-Gothic building

The writing of this article was actuated by the discovery of a manuscript, that contained the story of the building of the neo-Gothic St. Willibrordus church in Kloosterburen, written by the parish priest, called Antonius Kerkhof, who set up this enterprise.

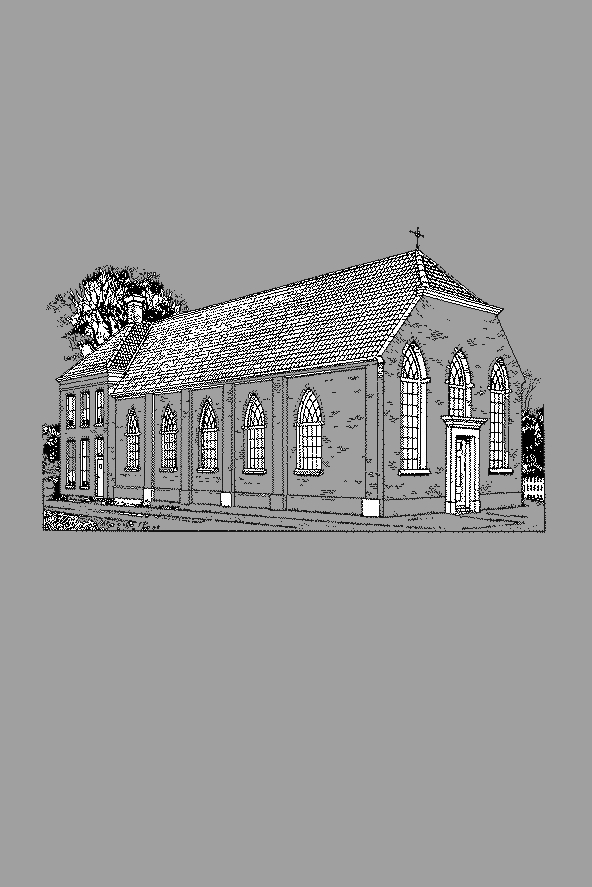

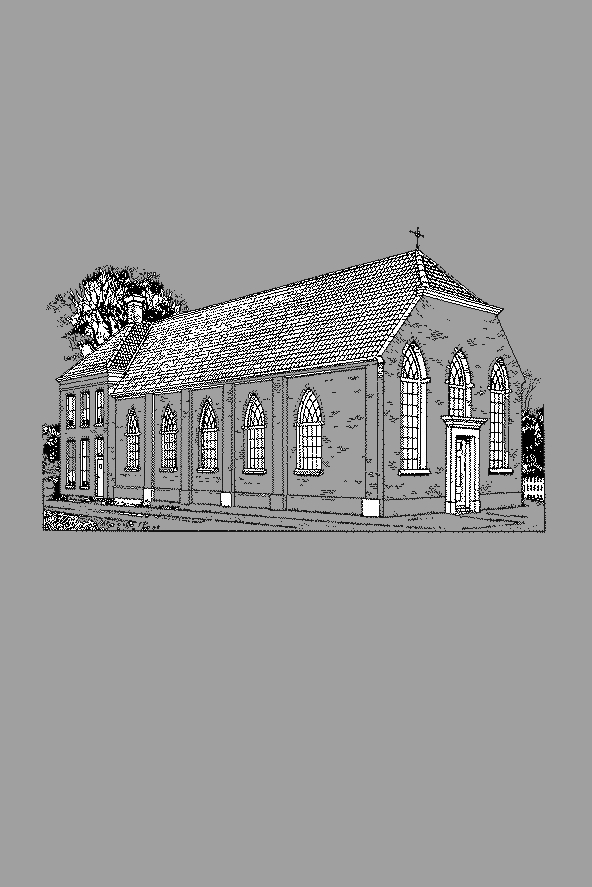

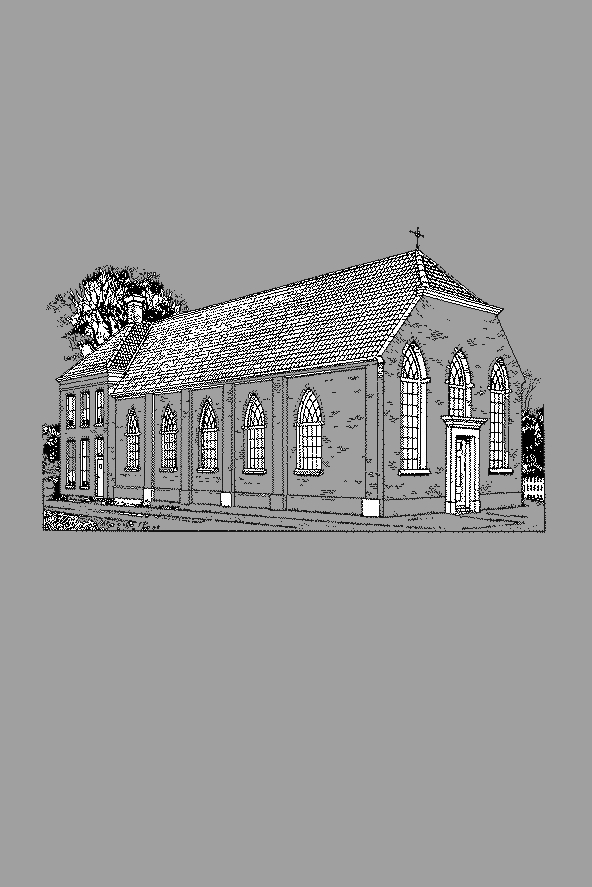

In his logbook he described the preparation for the building, the decision making, the funding, the consultations with the architect P.J.H. Cuypers and the church authorities in 1867/68. Finally he gave a report of how and when the building was realized. The church, which had served the parish up to then – a real waterstaatskerk – was, true enough, still in a good condition, but gradually it had become too small. Both churches may not have an important, but they do have an interesting place in the history of architecture. The first (built in 1842), because it is a representative of a good many churches, which were built under the auspices of the Department of Public Works in these decades. The second (1868/69), because it is a nice example of the adaptation of Cuypers’s neo-Gothic style to a small village in the province of Groningen and also because it is a unique specimen in one respect in Cuypers’s oeuvre, looking back as far as possible now.

The “Waterstaatsstijl”

This style is a hazy term, loaded with prejudices, which is often used and yet, has never been defined.

A waterstaatskerk is a church building, which was realized in the second quarter of the 19th century through the good offices of the civil servants of the Department of Public Works. The number of those churches is not small and the used forms and compositions diverge quite considerably. In the traditional view both the impressive St. Anthonius van Padua (i.e. the Mozes and Aäronkerk on the Waterlooplein (=Waterloo Place) in Amsterdam, 1841, architect T.F. Suys) and the comparatively unsightly Willibrorduskerk in Kloosterburen belong to the same waterstaatsstyle. In these circumstances, when there is no unity in character and characteristic details, there can be no question of giving a usable content to the term “Waterstaatsstijl”, so that it is wise to steer clear of this term.

It is not necessary to object to the name of “waterstaatskerk”, if it is certain, that civil servants of the Department of Public Works were concerned in the building process. By the way, this term does not say much, for the part that the civil servants played, was not always the same. Because of its many competences and capabilities the influence of this government authority on the early 19th century architecture in The Netherlands has been so important, that it seems right to pay some attention to the organization and field of activity of it, though it can only be partly an outline within the compass of this article.

The “Waterstaat”

The Waterstaat is, just like the other government authorities, an organization dating from the French period (1806-1813). Before that period the provincial and local authorities were responsible for the sea- and river dikes, canals, locks and sluices, bridges and roads. After a number of reorganizations of structure and competences of this department, a framework came into existence in 1819, which was maintained till the middle of the century, which is important for this survey.

The Department of Public Works was part of the Department of Home Affairs (apart from 1830/31); the management was executed by an inspector general, four inspectors, some chief engineers and other engineers. The management included those public works of which the costs were paid by the public funds; the department exercised supervision on the execution of all works of general interest, so on public buildings as well.

In the provinces the Department was managed by the chief engineers, who were, in their turn, in the service of the “Staatsraad”, Gouverneur des Konings (Lord Lieutenant of the King) and the Provincial States (but they were appointed by the government in The Hague). Together with some surveyors the chief engineers did their job. This task covered a great variety of works, like docks, dikings, factories, prisons, fortresses, sea-defence walls, roads, watermills, drainage mills, official residences, toll-houses, schools. Since 1824 the supervision on the building of churches was added.

It is not right to label this influence of the government as sheer paternalism or centralism. By causes which are not properly investigated, the professional skills and creative power of the Dutch building experts – whether designers or executors – were at a comparatively low level around the beginning of the 19th century. Waterstaat started to act as an authority, which could check expertly and, if necessary, could correct the designs, specifications and estimates of building experts – or those who posed as experts.

The notes of modification of the waterstaat, which are to be found in the provincial archives, show clearly, that it was not a question of bureaucratic interference: there are advices for another installation of a window to get a better incidence of light, there is for example some criticism on a construction which is not solid enough, doors which are too narrow and the forgetting of a foot plank on the beams of the ceiling for any possible repairs of the dormer in future. When a somehow uncertain church government asked for it, the Waterstaat drafted an estimate and for the church in Kloosterburen they even drafted an advert for the public tender.

The government of the country demanded the supervision of the building. Not only to get the guarantee that the conditions which were made, if any, were met, but especially in those cases, that the parish community had asked the state (i.e. the king) a complementary subsidy for the new building, as it was often done by small rural districts in this period of economic weakness and stagnation. In those cases supervision was necessary to prevent that the money which was made available, was not spent on other aims and, moreover, that the money was spent as good as possible. It goes without saying that the influence of Waterstaat was considerably more when a subsidized church was realized than when a not-subsidized church was built. The influence was also more when a church was designed and estimated by a building expert, who was not very capable, than when a church was built by an experienced, capable architect. In some cases it happened in the province of Groningen in the eightteen-forties, that Waterstaat was responsible for the complete job, when the church government did not succeed in finding a dependable and capable architect.

The training of the engineers of the Waterstaat became a matter of the state in the same time that the Waterstaat was made into a national organization. In 1805 the “General theoretical and practical school for artillery, military engineering and Waterstaat” was founded in Amersfoort. In 1806 the school was transferred to The Hague, in 1810 it was closed and in 1814 it was reopened in Delft.

In 1828 the training of the candidate-engineers of the Department together with the one of the officers was transferred to the Royal Academy in Breda, but in 1842 the engineers’ training – now for the first time apart from the military training – returned to Delft and was called the Koninklijke (=Royal) Delftse Academie, which changed into the Polytechnic School in 1868 and in 1905 into the nowadays still existing University of Technology. We do not know anything about the quality of the architectural training which was given to the intended engineers. An investigation into this matter could add important information to the understanding of the early 19th century architecture; maybe it could give an explanation for the remarkable similarities, which exist between several waterstaatskerken in different parts of the country.

The Waterstaat did not only supervise the building of new catholic churches, though this impression was created formerly. The Department worked for all religious modalities, as the procedure was the same for Protestant, Catholic and Jewish parishes: the Ministry of Public Worship had to be asked permission for the purchase of land and for the building of a church in accordance with an enclosed estimate, design, specification and finance plan (when in addition a subsidy was asked, thàt request had to be made to the king straightaway).

This ministry sent the technical information via the Gouverneur des Konings (=Lord Lieutenant) to the provincial chief engineer, who had it investigated by one of his surveyors (in Groningen there were ten in the forties). That investigation, processed into a note, was evaluated by the chief engineer, after which the document went back the hierarchical way and finally also decided if the Consenting Royal Decree would follow. As the archives of the chief engineer contain the complete correspondence (with the exception of the internal correspondence in The Hague) in original letters or copies, the archives of the Department offer an abundance of information about the history of architecture and the local church history.

The first St. Willibrorduskerk in Kloosterburen.

Since the Reformation the parish of Den Hoorn had been the only one in the region of the Marne, so that the Catholics of Kloosterburen had to put up with the trip to the church of Den Hoorn for their religious services. However, the condition of the roads was, especially in winter, extremely bad and when the number of Catholics in Kloosterburen started to grow in the beginning of the 19th century, plans were made for the foundation of a church and parish of their own.

In December 1838 a committee, consisting of Catholics from Kloosterburen, addressed a petition to the Director-general of the affairs of Roman Catholic worship to be allowed to build a church and a parsonage in accordance with the enclosed designs, specification and estimate (9408 guilders). Not before March 1840 the Gouverneur (Lord Lieutenant) of the province of Groningen asked the chief engineer A.C. Kros to evaluate the building plan, after which the latter passed the task on to his surveyor W.I. Hasselbach.

These original plans are dated 24 December 1838 and are signed by G. Dusseldorp. The enclosed designs have gone lost. Hasselbach’s note with suggestions of improvements was ready in August. With some modifications of the chief the document was placed before the committee of Kloosterburen that agreed with it. In March 1841 the Gouverneur asked Kros to make designs, a specification and an estimate in accordance with the improved version. With these plans, finished in August, the church was built. The chief engineer Kros signed them; they were, however, Hasselbach’s work.

The public tender of the work was on 25 February 1842. On 2 May the building started; within two months the church and the parsonage were covered in. The consecration took place on 27 September and in January 1843 the first priest of the new parish of Kloosterburen was appointed.

During the building, which cost about 14,000 guilders and for which a subsidy of 4000 guilders was provided, the daily supervision was given to a master-carpenter from the neighbouring village of Wehe, H.P. Noordhoek. Hasselbach was commissioned to make visits of inspection at intervals. It was not necessary to do it often: a colleague, who supervised the building of the new Netherlands Reformed church in Kloosterburen in 1843, only came to survey seven times during the building period. According to the designs the church was, forced by the tight financial situation, a church of the utmost simplicity, just a simple rectangular building. It is characteristic of this worried time, that even the economical plans of Kloosterburen for a finer church were too luxurious. The parsonage was built against the chancel, probably to economize on materials and fuel costs. This style of building was not unusual: the small catholic waterstaats churches of Zuidhorn, Assen and Sappemeer and their parsonages had one roof as well.

The total length was more than 30 metres (the church was 23.2 and the parsonage was 7.2 metres), the width was 10, the height to the ridge was more than 11 metres. The rectangular building had a loft above the entrance and had a wooden ceiling. The exterior reminded more of a barn than a church, even though the cast iron pointed arch windows and the cross on the roof referred to the function of the building.

The appearance of the pointed arch form of the windows could not be seen apart from the birth of the neo-Gothic style in The Netherlands, the new style which was applied here and there in the thirties, although the designs of the St. Willibrorduskerk show clearly, that it was not a neo-Gothic church: the pointed arch windows alone are not characteristic enough for such a qualification. That the pointed arches were applied here is probably not a result from a romantic interest in the Middle Ages, but an expression of conservatism (or sense of tradition): that many of the old village churches in the province of Groningen were mediaeval was practically unknown. Probably this type of window was used, because this form as no other symbolized the religious destination of the building. This is not only valid for Catholics: the Netherlands Reformed church of Kloosterburen has the same kind of windows.

The St. Willibrordus had another characteristic, which is associated with the traditions of the Middle Ages; it was oriented: the church faced east towards Jerusalem. That was not necessary because of the site; there was enough space around the church. Just the fact that the entrance could not be on the main road, makes it probable, that evidently the orientation was important, so it was done on purpose. This would mean that, contrary to Alberdingk Thijm ’s opinion, the knowledge of this significant mediaeval tradition had not gone lost in the strongly isolated country: the church ( a clandestine one) of Sappemeer, which was founded in 1761, was also oriented.

The second St. Williborduskerk.

After twenty-five years, in 1867, the parish had grown to such an extent, that the church was thought to be too small. Probably also too shabby: the social and liturgical development of Dutch Catholicism started to make higher demands on the building and furnishing of the churches. What happened from 1867 to 1869, after his parishioners had expressed their wish for a larger church, was described by the priest A. Kerkhof in the following report:

“The existing church was a real waterstaatskerk, to be true it was strong, built with solid mortar and bricks of good quality, but with a wooden ceiling, painted blue and tiled and for the parish of that time too small. On a winter day, when it was freezing, the ceiling started to drip because of the heat of foot-warmers and people, so that sometimes umbrellas had to be used, except for the altar, above which the ceiling was covered with straw (in my time it did not start dripping until the Holy Mass was ended). I did not start the idea of building a new church, but the parishioners began to talk about it themselves: “We really should have a new church, for this one is much too small.” “Yes, people, that may be true, but I do not think it is necessary; nobody stands in the way. But you will understand indeed: if I have to build a new church, then we do build a new church and that will cost money and I do not have any (there was still a debt of ƒ 5,000.- of the old church, which had to be redeemed first). If you have the money for the job, I do not know.” And yes, there were rix dollars enough. “If that is true, I shall do my best.”

Anyhow, I took the matter up. I discussed it with the architect Cuypers from Amsterdam, who was working on the parsonage in Groningen at that time and with whom I had made acquaintance during the building of the church in Ulft. He came to Kloosterburen and he would make a design for me then. I wrote to the Serene Highness Most Reverend J. Zwijsen, the archbishop of Utrecht, about my plan to build a new church in Kloosterburen. Monseigneur approved of it and referred to the architect Wennekers, who had built more churches in the north.

I wrote back to Monseigneur and asked if the reference to the architect Wennekers was an order or just an advice, because I was already negotiating with the architect Cuypers. Then Monseigneur replied: if you have made an agreement with the architect Cuypers, then that is all right, but be careful that you do not build beyond the means of the parish, for the architect Cuypers builds expensively and by public tender one is often disappointed, because the estimate is too low and the description is far beyond the estimate.

Meanwhile I released my plan to build a new church to the parish, if I would get enough support from the parishioners. ( K. wrote, that a subscription list brought in 27,000 guilders). I wrote it to Cuypers: he should make haste with the job now. He made a design and specification, which had to be checked and approved by the government architects.

The latter made some remarks about the structure, about which I informed Cuypers and he replied to the gentlemen. I requested Cuypers to make a rough estimate and besides I informed him about the letter of Monseigneur the Archbishop. Thereupon Cuypers replied to me: “Tell Monseigneur, that I guarantee the estimate and if by public tender it appears not to be contracted for it, then the church government of Kloosterburen can have the job carried out according to specification and designs, at choice by whom under conscientious supervision in order to have it carried out well. And if the church government can reduce expenses somehow, either by the purchase of materials or otherwise, then this will be an advantage for the church. What will go beyond the estimate during the building I shall pay out of my pocket, so that in no circumstances the expenses will go beyond the estimate.”

The estimate was ƒ 50,000.-: ƒ 30,000.- for the church and ƒ 20,000.- for the tower (8 metres). (the tower, however, was shortened and I think it measures 7 metres). I wrote this result and Cuypers’s reply to the archbishop, whereupon I got a favourable fiat.

Now there was still a problem concerning the site. The old church was built on the canal to the road. As the new church would get another direction, with the tower facing the road, the site was either too narrow or too short, so that necessarily I had to buy ground beyond the canal (purchase followed).

Because the plans laid on the table of the government architects the matter dragged on and tenders could not be invited before May. In November the work had to be covered and finished to such an extent, that the church could be put into use, if necessary.

On the fifth of May the tender took place. There were five tenderers, the highest of whom was ƒ 72,000.- and the lowest was ƒ 55,000.-. Yes, Mr Cuypers, and now ? Reply: “I stick to my word.”

Now then we will do the same. Cuypers had taken with him a conscientious supervisor: Mr J.J. van Langelaar from Amsterdam, one of his most capable supervisors. On Cuypers’s advice the church government decided to charge this Van Langelaar with the execution of the work. He acquitted himself masterly of his task. “He may be a Protestant”, Cuypers said, “but you could confide in his thoroughness.” (The contract was not awarded, it was decided to build under our own control).

Now to work: an advert in the newspaper for an entry of bricks and sending of several samples. Well, several samples and reports of prices arrived. However, as we needed the bricks soon, we had a shipload of several tenderers sent in as samples. In this way we got enough bricks to start with. Here I received from one of those suppliers a letter, in which I was reproached for my way of acting, it being a sly trick. Well, in fact it was a bit like that (but we were saved).

The church was built right across the old church and that is why we had to build a temporary church. The site for that was the ground I had just bought. On Sunday I notified the parish: “Tomorrow there will be a sung Mass, the last Mass in this church and immediately after that we will begin to demolish this church and build a temporary church after that, which necessarily has to be ready in eight days, before next Sunday. The parishioners are politely requested to see to it, that there will be enough persons present here to help me with the job.”

On Monday the church was full of people and they started to work straightaway. A long ladder was put against the church, I climbed it myself and took the first tiles from the roof and so thereupon they passed the tiles from hand to hand in the direction of the temporary church. Everything went cheerfully and quickly. The sidewalls of the temporary church were erected from the boards of the roof and truly, I could celebrate the divine services in the temporary church next Sunday. Now the walls had to be demolished: bricklayer, carpenter, smith, all came. They enjoyed it: at my kind request there came enough persons with the necessary tools to chip bricks. Sixty thousand bricks were cleaned and used for the foundations of the new church. The site was put to right and meanwhile new bricks had arrived, unloaded in Molenrij and brought to the site by farmers: all personal service and carriage were done by the parishioners for the greater part.

On the fifth of June they started with the foundations and half November I could hold divine services in the new church. I took part in the job myself, many beads of perspiration fell on the ground and the bricks, I encouraged and set the work going. The freestone was brought unfinished to the site and there it was finished. From half December to half January no work was done. Then it was resumed and finished. This building under our own control caused anxiety for me: I had to discuss everything with the supervisor Van Langelaar, consult everything, conclude contracts and yes… on Saturday I had to see to it, that I had money to pay the workmen. At the merchant-shopkeeper Kramer I had my discount bank.

When I was short of money (for I paid cash at a discount of 2 per cent as far as possible), I went on the road and borrowed (of course without interest). I must say, they helped me loyally. Finally, having calculated everything, we were still four thousand guilders under the estimate. We owe this result certainly for a great part to tact and discretion of Mr Van Langelaar.”

In the summer of 1869 the new St. Willibrordus was completed. Catholics and non-Catholics will have had to get accustomed to the fact, that the old tower (1658) of the Netherlands Reformed church did not dominate the silhouette of the village anymore, especially because the religious contradictions were hard and sharper in those days.

The new church was, after the humble, barn-like building, a manifestation of a parish, which was not poor anymore, had obtained a greater self-respect and which emphasized its religiousness. The neo-Gothic church, which is free-standing on all sides, is some dozens of metres from the main road, the chancel facing south. The short, square tower has been crowned with an octahedral spire. It is half in front of the church and half in the first bay of the nave; the first floor acts as a singers and organ loft.

The nave has a length of five bays. The arms of the transept protrude a bit. They are narrow and, in conformity with their width, not very high as well; their pitched roof links up to the pitched roof of the nave, which is, in comparison with Cuypers’s usual roofs, not very steep. Possibly this is a consequence of the lowering of the tower, because of which a lower ridge was necessary in connection with the linking-up of the roof. Especially should be thought of the fact, that the roof seems much lower and wider since the dormers were removed during the restoration of the church (1969).

The part of the chancel, enlarged by Cuypers’s son Joseph (in 1903), consists of a nave with a polygonal enclosure, which is a bit lower than the main nave, has two small side aisles, the size of one bay, and is covered with a lean-to roof.

The exterior creates the impression of soberness; the few component parts are uncomplicated and are grouped in a simple way. The decoration has been applied sparsely and consists of practically almost exclusively simple variations in the masonry.

The elaboration of the interior is at the least as polished and simple of character: fair faced masonry, thin pillars of sandstone (a bit thicker in the transept crossing), vaults of yellow sandstone (groined vaulting in the nave), the arms of the transept and the bays of the side aisles have other types of vaults (but I do not know the English terms / Anja van Dam), the church has a nave and two side aisles and a bipartite elevation.

Comparison of the interior and exterior is surprising, because of the fact that though the church seems to be a pseudo-basilica ( a nave with two lower side aisles, but without skylights), the interior really shows us a complete basilica: the nave is lighted by daylight through the windows at the top. This very peculiar and rare intermediate form of a basilica and a pseudo-basilica are, perhaps, a consequence of the poor financial elbow room of the architect: this church was cheaper than a basilica and lighter and more spacious than a pseudo-basilica. The solution, however, is a compromise, which is as unexpected as surprising in Cuypers’s oeuvre, for he always rejected in principle the “dishonest” building during his career: the “pseudo-architecture”, by which – like here – the suggestion of the exterior does not fit in with the interior. The theory of the Gothic Revival – especially Cuypers’s Gothic Revival – set against that, that the exterior should not be in contradiction with the interior and that the building plan of the interior should be clear from the exterior. That Kloosterburen was far away from the centre of the country (and so, from potential, influential critics), must have made it easier for Cuypers to deviate so much from his principle. There are one or two other examples of “pseudo-architecture” in his oeuvre, but a more important example than the church of Kloosterburen does not seem to be found.

Cuypers succeeded in adapting the nice little church to the surroundings: it is a typical village church in its simplicity. Typical, because Cuypers has obviously been inspired by the contours and the form of the mediaeval village churches in Groningen and Friesland. This was not the case with the St. Vituskerk in Blauwhuis (Friesland), which was built at almost the same time, a much larger church in a village as small as Kloosterburen, with which the St. Willibrorduskerk has several details in common. Both churches are the first two churches that Cuypers built in the northern part of the country and therefore they are the first representatives of the phase in the Dutch Gothic Revival, which was in technical and ideal respect exceedingly important for the development of the architecture.

The priest of Kloosterburen could not have been aware of that importance. But (you understand that if I have to build a church, then we do build a church) he must have been fully alive to the prestige that his enterprise got, because of the co-operation of the architect, who had become famous in the whole country, while the Catholics elsewhere in the province had to remain content with their “waterstaatkerkjes”.

A. van der Woud

The original Catholic Church opened in 1842. A new one was built in 1868, expanded in 1904 Restoration(s) 1970.